COVID-19 in developing countries: whatever it takes? edit

While COVID-19 is being most virulent today in Europe and North America, the pandemic has now started taking hold in the emerging and developing world, with many countries experiencing increased numbers of cases. Latin America and Africa are becoming the next epicenters as infection and death rates are on the rise. Countries, in particular those that are more connected to the world economy, are already experiencing the economic impact: collapse in commodity prices, falling tourists’ revenues, drop in remittances, massive capital outflows. There is need for a global and effective response to the virus. Failing to do that, the risk of becoming endemic in the developing world and coming back to the developed world in a second or a third wave, is looming.

As the pandemic spreads, emerging market and developing countries are facing a triple shock: a health shock (not well equipped health system, density of populations in some areas), a global spillover (falling trade, access to finance, falling remittances and tourism), and a commodity price shock (tumbling oil prices). To overcome this halt, they need financing. Delivering a generous debt relief package is essential to allow countries respond to the crisis. But this would not be enough. There is need for a major multilateral response in building and supporting health systems. The institutional infrastructure and the funding mechanisms are there (e.g. Gavi, the Global Fund), as well as the track record of dealing with health crises (e.g. HIV, Polio). What is missing, are the financial resources.

There are four particular features that developing nations exhibit, that make the economic aspect of this crisis very difficult. First, is low income. While for a middle class family in London or Germany not working for a month or two may be possible and manageable, that is not the case for families in emerging countries whose income is very much at subsistence level.

Second, is labor market informality. Under a formal labor contract, a company provides insurance (while it may also receive some support from the central bank or the government) and thus keeps paying its employees even if they are not producing. However, in many emerging economies – even in middle income or upper middle income emerging economies – one half to two-thirds of the labor force is employed informally. Therefore, the feature that could provide insurance is absent.

Third is monetary financing. Most emerging economies cannot resort to monetary financing in the way that developed countries have. During the 2007-08 crisis the US Fed multiplied its balance sheet by a factor of 5.2 (from $870 billion in August 2007 to $4.5 trillion in January 2015) and inflation did not budge. However, if a developing country (e.g. Argentina) tried that, inflation would jump and the value of the peso would crash. Thus, by simply printing domestic currency to deal with the emergency in any substantial quantities is not a way out.

Fourth, is foreign currency. What emerging countries need, is not just domestic currency but foreign currency. If both the private and the public sector run a deficit, the current account (the sum of the two) will skyrocket. And the question is where do you get the money (e.g. USD, EUR, or JPY) to finance a large current account? While more developed countries are able to put together anti-crisis packages that are as large as 10% of GDP (e.g. Australia, Germany, the US), emerging countries cannot afford to reach these levels (even though their needs are many).

Assuming that emerging countries were to put in emergency plans that required a large government deficit of around 3% of GDP, it will imply (keeping the private sector deficit frozen) a current account deficit of about 3% of GDP. Put that into perspective, 3% of Latin America’s GDP is around $164 billion. For comparison, the amount that has been disbursed by the IMF in response to the COVID-19 crisis is less than $1 billion, while the IMF’s total capacity to lend to Latin America, is less than 1% of the region's GDP. This is a very large gap that could not be financed by business as usual.

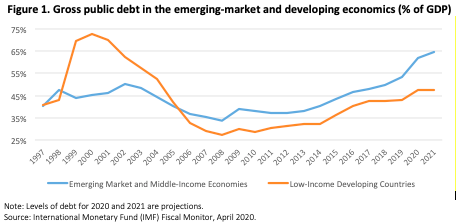

Latest projections put the gross (internal and external) public debt of emerging-market and developing countries at the range of 62% and 47% of their GDP in 2020, respectively (Figure 1), while the sudden stop in capital flows in emerging markets, has created a hole of around $66 billion since the beginning of March. Given the insufficient levels of internal reserves and borrowing from local markets, emerging market countries would need at least $2.5 trillion in financial resources in order to get through the pandemic. The question then arises: How such gap can be financed?

One way is via debt markets. Social bonds, for example, can channel important amounts of money to fight the COVID-19 global emergency. Supranational banks, governments and corporates have an important role to play in that direction. Over the last weeks, the African Development Bank (AfDB), the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IF), among others, have raised capital by issuing social bonds that support emerging markets and developing countries. As for the sovereign social bond market, while it presents an opportunity for governments to apply its external debt towards public policy goals, it is still in a nascent stage.

Although governments can issue social bonds to fight COVID-19, this will increase debt levels, retard growth, reduce spending flexibility and crowd out private investors from capital markets. It will also make some countries reluctant to use their money for paying the debt of an emerging country. Moreover, it is hard to imagine a very large package going to an emerging country while the country remains under great pressure to be current on their payments. Therefore, alongside a support package there should be some kind of a temporary debt standstill.

An alternatively, and perhaps more viable solution, is through a different type of swap arrangements than those that are currently available between the world's leading central banks and emerging economies. For example, only a very small group of emerging countries (i.e. Brazil, Mexico, Korea, Singapore) can currency benefit under the FED’s swap arrangements. On one hand this is understandable, as the Fed does not want to take on the risk associated with a dozen or more of emerging economies. However, the FED could potentially take on IMF risk, and then the IMF will have a swap arrangement with the FED (or the bank of England, the ECB, the BoJ) and in turn re-lend those resources. In that case, the major central banks have IMF risk on their books and not from emerging economies.

By hook or by crook, the operative phrase here is ‘whatever it takes’. Mario Draghi said he would do whatever it takes to save the Euro, while President George W. Bush said he would do whatever it takes to defend American security after 9/11. The question therefore is whether the world community does whatever it takes to address this huge, dangerous and painful crisis in developing countries.

Did you enjoy this article? close